Hello and welcome back to the SCARABsolutions Ancient Art Podcast. In our last episode on the Art Institute of Chicago’s Corinthian pyxis, we saw how the early Archaic Greeks of the Orientalizing Period incorporate stylistic elements and ideas from their Near Eastern neighbors and also from their own Bronze Age ancestors. We looked at the emergence of monumental Greek temple architecture with its unprecedented massively impressive pedimental sculpture. And ultimately we came to understand how the Greeks paid homage to their Mycenaean Bronze Age ancestors by employing scenes of ferocious beasts and fiendish monsters on these early temple pediments. They did this as a means of confronting the viewer, engaging with them and conditioning their psyche for approaching the divine, just as the Mycenaeans did half a millennium earlier at the entrance to the great city of Mycenae. And on a far more diminutive, personal scale, we see this same confrontational conditioning effect employed on the funerary vessels of this early Archaic period in Ancient Greece as a sort of memento mori, a reminder of our ultimate fate.

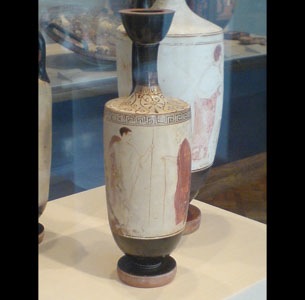

In this episode, I want us to take a look at a significantly later example of Greek pottery and vase painting, also at the Art Institute of Chicago. This is an Attic white-ground ware lekythos from around 450-440 BC attributed to the Achilles Painter. OK … what does all that mean? Well, you’ll often come across the term “Attic” on gallery labels. That’s got nothing to do with where you keep your Christmas lights. Attic means it’s from Attica, which is the region of Greece that surrounds Athens. Aha! … Moving along now. “White-ground ware!?” See, you got yer black figure vase painting and yer red figure vase painting … and then you got your white-ground ware, because the figures are on a white background and “ware” is just the fancy word for ceramics … you know, like dinner ware. And finally a lekythos is a specific type of Ancient Greek pottery vessel usually in a tall slender vase-like shape with a tight spout and a handle, but you come across small more squat versions too. The lekythos was specifically use as a decanter for oil, mostly olive oil for Ancient Greek athletes. Now, the Greeks lived in a time before the invention of soap. Filthy buggers!? Not really. See, olive oil is an exceptionally good cleaning agent (not to mention a common ingredient in some exotic old-fashioned soaps). After a long day of rolling around with your classmates naked in the sand at the gymnasium, Greek athletes would rub olive oil on their lean, tight flesh. They’d then take a small curved metal tool called a strigil and scrape it along their skin, removing the oil and all the grime, sweat, and guck. Don’t believe me? Next time you take off a day-old BAND-AID® and it leaves behind that yucky glue residue, rub a little olive oil over it for a few seconds and presto! — ancient goo-begone. [This does not necessarily constitute an endorsement, neither expressed nor implied, of the aforementioned products BAND-AID® brand bandages and Goo Begone or any similar or related products on the part of the author or his affiliates; use at your own risk; do not attempt this at home; yadda yadda, etc etc.]

Before we dive headlong into the subject matter of this lekythos, I want to explain why the painted surface is not nearly in as good condition as most of the black and red figure vases you’ll spot at the Art Institute. You see, in the white-ground technique, the white background was painted onto the surface of the vessel after it had been fired and then the figures were painted on top of that. All the decoration of black or red figure vases was applied before the firing process as slip (not actually paint) and then fired, so baking the decoration onto the surface so it ain’t goin’ nowhere. Paint applied to the surface after firing, however, isn’t as durable and it’s prone to flaking over the eons.

The scene decorating this lekythos depicts a gray-haired elderly man with a long red cloak leaning on a cane. He looks forward into the eyes of a youthful mostly-nude male figure with a shield strapped to his back and holding a spear. The fact that the youth is nude indicates his function as a warrior. (And the shield and spear kinda help us draw that conclusion too.) Warriors in Ancient Greece, of course, didn’t march out onto the battlefield in the nude, not unless they had a few too many at the feast the night before. No, they were fully armored with a sturdy breastplate, greaves on the legs, and a helmet. Excavations in the latter part of the 20th century at Midea near Mycenae actually unearthed a magnificent Bronze Age Mycenaean cuirass or a breastplate from the 15th century BC, the time of the great heroic warriors whose legacy inspired the later epics, now in the Archaeological Museum of Nauplion in Greece. Check out the website — scarabsolutions.com — for a link to an image and description of the armor and the excavations at Midea. There’s also an interesting article in the March/April 2007 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review called “Historic Homer: Did It Happen?” which talks about this breastplate and other Mycenaean-period historical accuracies in the Iliad and Odyssey.

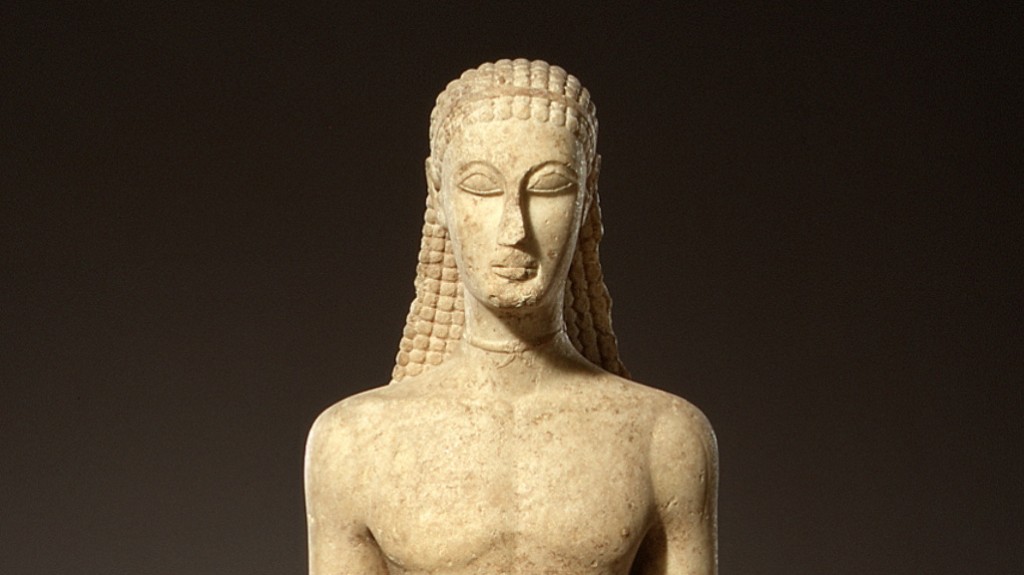

Despite the obvious use of armor, however, Greek artists imagined their mythological heroes were in fact nude. Throughout Ancient Greek vase painting we encounter the nude warrior, be it Hercules, Achilles, Hector, or any other heroic mythic warrior. Many a Greek male was fond of casting himself in the light of the mythic warrior, particularly upon death through the use of the nude male kouros statue as a headstone. The kouros is the earliest form of freestanding monumental Greek sculpture in the round, which finds its origin around the time of the Orientalizing Period, which we covered last time when looked at the pyxis. Perhaps a similar sort of desired effect is being attempted here — to cast the deceased in the light of the heroic warriors of yore. Remember, just about all the Ancient Greek vases you encounter in museum collections were actually grave goods. One might be inclined to interpret this scene depicted here as a father figure bidding farewell to the youth; their final goodbye before the youth marches off to battle. Perhaps the last time they will ever see each other … alive, at least. Neither figure has an expression of overwhelming emotion. They both bear a sober countenance, not betraying their torn spirits within.

Think about the difference in the way I’m describing the subject matter of this vase painting compared to the Corinthian pyxis from a century earlier. We’re trying to get inside the heads of the figures represented on the lekythos; we’re looking at a scene from some dreamt-up story. There’s definitely some sort of context here, in contrast to the decoration on the pyxis, where the creatures are outside of any context, any narrative or story. This is a big change taking place in late 6th, early 5th century Greek vase painting – a movement away from representations of ferocious confrontational beasts towards narrative scenes. Sure, representations of the Homeric epics go way back, but the narrative becomes firmly entrenched only in the mid to late Archaic Period, pushing aside the decorative flower patterns and the prominence of confrontational beasts common to the Orientalizing Period.

Beyond the heroic mythologized warrior, the nude in Ancient Greece also fires another neuron. I’m talking about the Greek athlete. Unlike the imaginary mythical nude hero, Greek athletes did in fact compete in the nude. Easy there tiger. The representation of this youth in the nude might draw us in two different directions. While all geared up, the youth is clearly preparing to head off for battle, but this solemn goodbye reminds us of the other activity of Greek youths — athletics, which perhaps the old man wishes the youth would sooner be doing before heading off to battle. And don’t forget the vessel on which this scene is depicted — a lekythos — a jar for an athlete’s oil bath. So what’s going on here? Why is the artist conjuring up a scene that might tug us in two directions? Well, just as with the Corinthian pyxis that we looked at before, this lekythos is also a funerary vessel, a grave good. So, to take our train of imaginative thought one step further, perhaps we have a scene here reflecting an actual occurrence or some imagined, mythologized, heroicized occurrence of a youth slain in battle, the loss of innocence, no more will he enjoy sport at the gymnasium with his fellow companions. So, he’s buried with a lekythos to recapture the activities of youth and he’s portrayed here as a heroic warrior worthy of all honor. Just as with the pyxis, here too we have a memento mori.

We see a big change taking place in the Archaic period as Athens emerges as the new cultural superpower, soon eclipsing Corinth. Perhaps the most significant stamp that Athenians place on the Greek world is their interest in the human condition, in morality, justice, pride, and suffering. And this shows up in their vase painting not so much in the stories that they tell, but more so in the way that they tell their stories. The artist could have chose to memorialize the deceased as a fallen warrior among other glorious dead or in the moment of a heroic death on the battle field. Or he could have represented some other mythical hero like Hercules, Achilles, or Perseus, casting the deceased in a brighter light. Instead we see a different sort of narrative aesthetic evolving in Attic vase painting. Well, by this Late Classical period it’s pretty much well evolved. Instead of showing the height of physical action, instead we’re presented with a subdued anticlimactic moment of pause, the quiet before the storm. It’s up to the mind of the viewer, up to us, to complete the narrative in our minds. Granted, this narrative technique relies on a sort of familiarity with the story. In this case, we may not necessarily be familiar with the story, but different clues like the nude form of the youth, his armament, and his classical contaposto (that’s the stance he’s taking, like a statue of some hero) — these clues lead us to the conclusion that he’s a warrior and the old man seems to be engaging with him. The rest is our own speculation, but it’s an educated and informed speculation.

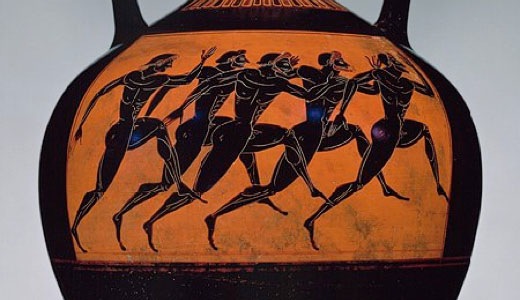

We encounter a lot of similar examples in Archaic and Classical Attic vase painting where a moment just before the height of the climax is represented, rather that showing all the gory details, and the artist relies on the viewer’s familiarity with the narrative to connect the dots and lead up to the climax in his or her mind. Here’s a fairly early and exemplary illustration, The Suicide of Ajax, an Attic black-figure amphora from around 540 BC by the very well known artist Exekias, now in the Château-Musée de Boulogne-sur-Mer (er … pardon my French). Ajax fought alongside Achilles in the Trojan War. In later myths and tragedies, he’s often elevated practically to the same status as Achilles. Alas, he’s probably most familiar to our contemporary audience as the big goober with the war hammer in the 2004 Hollywood production Troy, where Achilles is played by Brad Pitt. The Iliad just tells a fraction of the story of the siege of Troy. A lot happens between the Iliad and the Odyssey, where the latter recounts Odysseus’s journey back home from the 10 year-long siege. Apparently there were also other epics that told the stories of other warriors involved in the Trojan War beyond Achilles and Odysseus, sadly now lost – well … till somebody discovers a Greco-Roman mummy stuffed with papyrus fragments of some lost epic. … It’s not impossible.

But somewhere between the events of the Iliad and Odyssey, the unthinkable happens – Achilles is killed by Orlando Bloom … I mean, Paris. The armament of Achilles is to be rewarded to the most feared Greek soldier. It comes down to Odysseus and Ajax. They get into a big debate and the arms are finally awarded to Odysseus. There’re different accounts of what happens next, but one popular version says Ajax is completely distraught and goes into a mad rage, killing his Greek comrades left and right … or so he thought. Athena intervened and disguised the flocks as his fellow Greeks, so Ajax ended up only slaying the flocks. Completely embarrassed and distraught a second time for the harm he could have done, Ajax takes the sword of Hector (awarded to him after a stalemate battle against Hector), wanders off from the camp, and kills himself by burying the sword tip-up in the sand and impaling himself on it. So, here we see Ajax planting the sword, neatly packing down the earth around it. His shield leans lazily at the edge of the frame, his helmet and spears carefully placed atop. Incidentally, the spear was his weapon of choice, not the war hammer. And now we know what’s coming next. … Bleeehh! See, Exekias is relying on our familiarity with the story to bring us to the height the climax and all the gory bits without having to show the gory bits. It’s more engaging, less off-putting, and invites us to consider the Ajax’s state of mind. To ponder his pathos, the powerful Greek term for suffering and the human condition. And as if that’s not enough, Exekias also sneaks in a foreboding omen. Decorating the shield of Ajax is the fiendish Gorgon Medusa with snakes for hair, said to have been so hideously ugly that her gaze would turn you to stone. And above that is a glaring feline, similar devices to the ones we saw on the Corinthian pyxis. While it’s perfectly legitimate to have these devices decorating your shield (wouldn’t be a pretty sight to have that racing towards you on the battlefield), they also function in the context of the painting as ill omens of the impending tragic conclusion.

My goodness … how about that.

Thanks for listening. Don’t forget to hop on over to the website scarabsoltions.com for better quality images, links to external resources, and the extensive bibliography on Ancient art. I’m also adding transcripts for each episode, in case you’d prefer to read rather than listen to the podcast. That’ll also make it a lot easier if you want to revisit something you heard on the podcast, but can’t remember exactly where it was mentioned. Simply enter some keywords in the search box at scarabsolutions.com. And in case you haven’t noticed, you can leave your feedback for each individual episode at the website, if you have something nice to say or a particular axe to grind. You can also email me at scarabsolutions@mac.com. And while you’re at it, if you like the podcast, I invite you to go on over to iTunes and post a review. It’s gettin’ a little lonely out here. Take care and see ya soon on the SCARABsolutions Ancient Art Podcast.

©2007 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org